In those few minutes between plating the last dish and the first ring of the doorbell, my heart always races. I spread my clammy hands over my red-checkered, cotton apron and say a wordless prayer to whichever saint is listening—Martha, Julian, Genesius—that it will all go well, that friends will arrive, food will taste good, and conversation will flow.

This past Sunday, after a long, COVID-era hiatus, I hosted Friendsgiving again. Since my last time hosting, I’ve moved from Virginia to South Carolina, made new friends, learned new recipes. Sensing the late-autumn ennui of colder, shorter days, it seemed that a party—an informal, hors d’oeuvres and salad kind of fête—would be just the ticket. I sent out the text invite last Sunday, crashed through a tiring week in a waning semester, and made an early-morning grocery run to Greenville. And there I was, scattering mulling spices into a pot of warming garnacha, drizzling fig-balsamic syrup and rolled prosciutto, arranging manchego, antipasti, olives, and cold melon.

There’s a special aura to Friendsgiving; often, it’s for those of us who have logged many miles in the chaotic journeys of families and careers, who the universe brings to a common table at an unexpected place, to share the rituals of food and feast.

Growing up, I often celebrated Thanksgiving with my Italian-American grandparents, I associate that holiday with hard salamis, generous bowls of zuppa di pesce, and hard-crusted loaves of fresh Brooklyn bread. At the Bay Ridge restaurant owned by family friends, my grandfather always ordered the same dish at holiday meals, trippa, the lining of a cow’s stomach stewed in tomato sauce. It reminded him of the meals his mother made during the lean Depression-era years of his childhood: cheap, satisfying, nourishing. He ate the honeycomb-shaped trippa in contentment and peace, the meal of scarcity transformed into a meal of nostalgia and comfort.

Since he passed away last autumn, I find that this particular holiday feels empty—empty of the rituals and foods and people with whom I had once celebrated it. I was especially grateful to the friends who joined me for Friendsgiving, and for my friend Ashley, who hosted a traditional sit-down gathering last night.

The memory of my grandfather’s trippa and all it represented—in his life and in our family’s journey—has made me reflect on this year’s holiday. News outlets (CNN, AlJazeera, WaPo) have pounced on stories about the effects of inflation on Thanksgiving meals, although the country’s problems of food scarcity certainly exist beyond a single day or set of traditional dishes (I suspect issues of food costs and access are far muddier and more complex than such complaints about global inflation imply). It’s true, that for many of us in the position to host gatherings, it has required extra planning and budgeting. For me, such economic considerations only increase the sense of gratitude for the people I’ve celebrated with, and for the people whose hard work (agricultural, medical, social) resulted in us being able to gather in 2022 with a measure of cautious safety and optimism for the future.

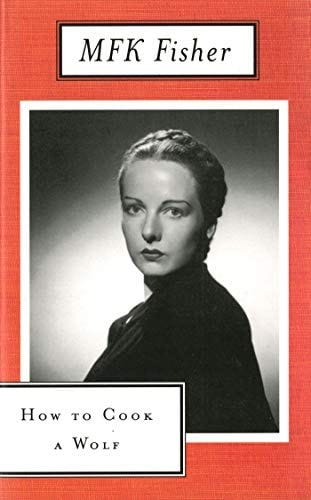

This month I reread M. F. K. Fisher’s How to Cook a Wolf (1942), a WWII-era modernist cookbook-of-sorts about the challenges facing a home cook amid scarcity and rationing programs. Fisher’s metaphorical wolf represents the looming fear of hunger, as well as the haunting traumas of her era. Part memoir, part satire of home economics and thrifty-housewife ideals, Fisher tells readers how to not only evade the wolf at the door, but to lure it, catch it, and carve it.

“I believe that one of the most dignified ways we are capable of, to assert and then reassert our dignity in the face of poverty and war’s fears and pains, is to nourish ourselves with all possible skill, delicacy, and ever-increasing enjoyment. And with our gastronomical growth will come, inevitably, knowledge and perception of a hundred other things, but mainly of ourselves. Then Fate, even tangled as it is with cold wars as well as hot, cannot harm us.” – M. F. K. Fisher, How to Cook a Wolf

My favorite chapter, “How to Make a Pigeon Cry,” blends the folklore of roast pigeon with a series of recipes both whimsical and hard-nosed: “I have eaten a great many pigeons here and there, and I know that the best was one I cooked in a cheap Dutch oven on a one-burner gas-plate in a miserable lodging. The wolf was at the door, and no mistake; until I filled the room with the smell of hot butter and red wine, his pungent breadth seeped through the keyhole in an almost visible cloud.” How to Cook a Wolf has generated a lot of interest during COVID, including an exhibition at the Center for Book Arts on “artworks that double as food stories and sources of solidarity during this unprecedented period” and great Eater piece by Anne Wallentine (whom you can find over at

), that focus on the ways that food rituals amid crisis can create a nourishing sense of community.In her incisive book Global Appetites, Allison Carruth (a grad school mentor from my UCLA days), describes how Fisher celebrates “the unruly individualism (if also the cultural and material capital) to cook creatively in a time of scarce resources and fuel shortages. Against the government’s edict for citizens to share alike, Fisher calls on her female readers to cook imaginatively and to eat selfishly” (69). At the heart of Fisher’s How to Cook a Wolf is a sense that the embodied, aesthetic pleasure of preparing and sharing a meal amid such conditions is an act of willful creativity and political resistance. It is also an act of mindfulness to practice even in times of plenty: in each of her thrifty recipe “tricks,” Fisher writes, “there is a basic thoughtfulness, a searching for the kernel in the nut, the bit in honest bread, the slow savor in a baked wished-for apple. It is this thoughtfulness we must hold onto, in peace or war, if we may continue to eat to live” (20).

After the party, I took off my apron and returned it, carefully folded, to its drawer. I sat on my sofa, utterly content, fully at peace with the world, listening to the last few songs I had added to my party playlist, and was grateful.

Wishing you all contentment, companionship, and calm this season.