This is the first in a series of posts about language in our world today.

When I taught English at Converse, I had a poster on my office door with a quote attributed to writer and public servant Nathaniel Hawthorne.

“Words – so innocent and powerless as they are, as standing in a dictionary, how potent for good or evil they become in the hands of one who knows how to combine them.”

In my blended career as an editor and scholar, part of what I do is curate words on a page, help them convey information, voices, stories. To me, this quote captures the ethical stakes of writing and of the humanities: to explore the complexity of our history and world, to offer philosophical frameworks to understand our experiences and those of others, to create works that give solace or spur important conversations. And, if needed, to offer critical resistance to established or emergent systems of harm.

Through and beyond the Inferno

As a way of processing the events of the past few weeks—events that have directly impacted higher education and civic tech—I’ve been rereading parts of Dante’s Divine Comedy, in particular, the circle of fraud, which—no surprises—is filled with political actors. Dante was deeply embroiled in the political conflicts of his day, and these provide much of the material in the Divine Comedy, in which spiritual and political ills are inextricably bound.

So, let’s go to the Malebolge of the Inferno. These are the ten concentric ditches in the eighth circle of Hell, which each address a different kind of fraud—fraudulent council, falsifiers of words, sowers of discord, hypocrites (Inf. 18-30). The whole second half of the Inferno is, arguably, a mediation on politics and language, on truth and betrayal.

The eighth circle of hell takes up a huge amount of real estate in the Inferno, and common theme in it is, as Teodolinda Barolini writes, “the utter distortion of language…here language is used not to comfort and to console and to communicate – language is used to betray.” The only circle lower than this is the ninth circle—the circle of Treachery, a frozen, wintery world of spiritual emptiness.

In the deepest rungs of hell, the greatest transgressions are those that use language to willfully harm—among them, those who betray their country, those who betray guests, and those who betray people who trust them.

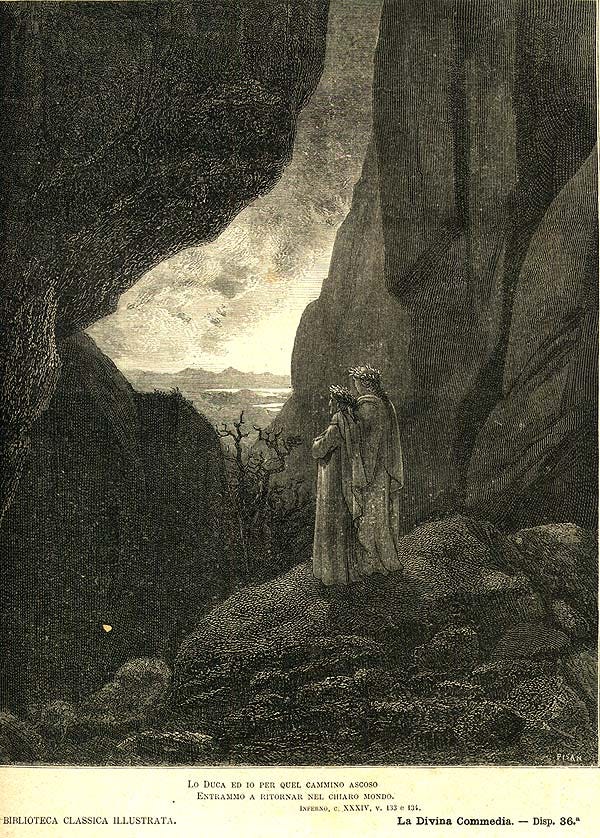

After traveling through the eighth and ninth circles of Inferno, where language was violence and did violence, the Dante-pilgrim finds himself in a place where words are redemptive, transformative.

The way out of hell is through a subterranean cavern that leads Dante and Virgil through the center of the world and to the southern hemisphere. The way is long and dark, and the two figures follow the sound of rushing water from a little stream. The Inferno ends with this stunning final verse: “we emerged to see – once more – the stars” (E quindi uscimmo a riveder le stelle) [Inf. 34.139, transl. Mandelbaum].

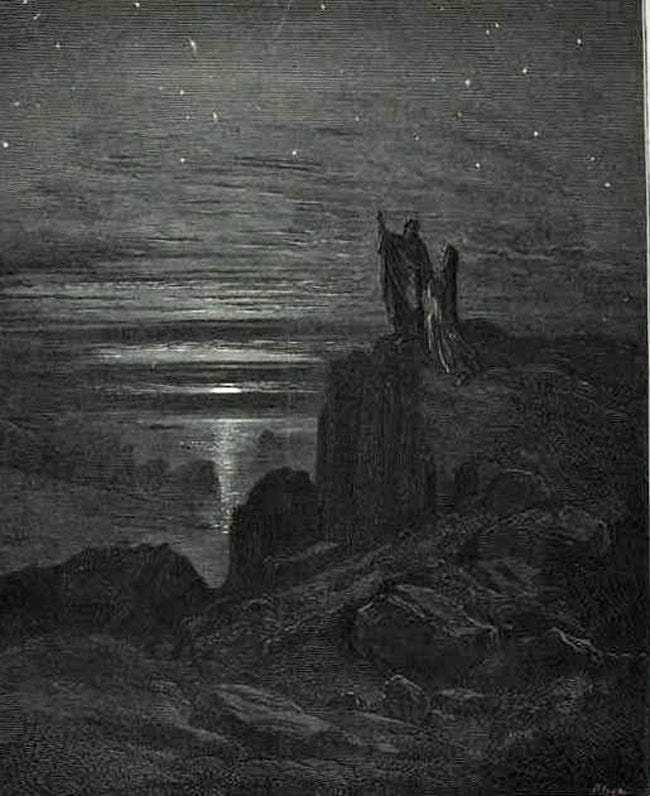

This is one of my favorite moments in the Divine Comedy. Dante and his guide emerge onto the island of Purgatory, and see the beauty of a “sapphire” sky just before dawn (Dolce color d’oriental zaffiro [Purg. 1.13]).

This is the place, in Dante’s cosmology, where hope begins. (If you remember Inferno 3, you’ll remember the inscription above the entry to Hell says, “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.” Having left Hell and arrived in Purgatory, the Dante-pilgrim witnesses the return of redemption, and the return of hope.)

Purgatory is utterly different from Inferno; it is an aboveground and emotionally complex terrain—a soul’s journey through remembrance of the transient beauties and affections of earthly life. Barolini writes, “In the Purgatorio the poet sings and caresses the beautiful earthly things that we are leaving behind: from the beauty of the sea and shore of Purgatorio 1, to the beauty of poetry sung to music in Purgatorio 2, to the beauty of friendship and art and home and family that we encounter so frequently in the pages of Purgatorio. The Purgatorio is the part of Dante’s poem that tugs on the heartstrings with its nostalgia for forms of beauty and solidarity that are exquisitely human.”

There’s an amazing detail in the first canto of the Purgatorio. The shoreline is lined with rushes that regrow miraculously when one is torn from the sand. Virgil, Dante’s guide and poetic mentor, wipes Dante’s tear-stained face, which is still covered in grime from the journey through hell, and then plucks a rush to gird him, which immediately regrows:

oh maraviglia! Ché qual elli scelse

l’umile pianta, cotal si rinacque

subitamente là onde l’avelse.

O wonder! For as he plucked the humble plant,

it was suddenly reborn, identical, where he had

uprooted it. (Purg. I. 134-36, trans. Durling)

This botanical allusion is to the mythological golden bough of the Aeneid (Virgil’s Latin epic)—a branch that Aeneas takes with him into the Underworld as a gift for Proserpina. In the Purgatorio, the rush that Virgil uses to draw together Dante’s robe is also a metonym for the Aeneid itself. This scene shows one poet comforting another through their work. It is also a prophetic scene that suggests that Dante’s work, too, will comfort its readers through the centuries.

The rushes, or reeds, that grow on the shoreline of Purgatory are, most likely, Cyperus papyrus, a wetland sedge, the material of early papyrus paper. The reeds symbolize not only spiritual regrowth but writing itself. Dante, as a poet, is suggesting that the labor of words is somehow regenerative—a labor of creating and preserving. A labor of consolation and community.

Here, the place where hope begins, is marked with the unlimited supply of writing material. To rewrite our stories anew. To see beauty once more, and to create again.

Language for hope or harm

The detail of the rushes from the Purgatorio links creative potential and spiritual growth. Ursula Le Guin makes a similar claim in her own guidance (and consolation) to writers:

Le Guin’s call-out of politicians feels especially timely (because, perhaps, it is also perennial).

Language—when it lies, when it silences truth, when it contradicts itself or cowers behind sarcasm and cruelty, when it willfully creates chaos—is transgressive.

As Atlantic writer Megan Garber writes, “Lies are not semantic. Lies can lead to violence—in some sense, they are violence.” I remember hearing an interview with Holocaust survivor Howard Chandler, who said, “It began with words.”

Words. Conveyors of ideas, carriers of hope, tools of harm.

The second part of Le Guin’s quote, though, is about words that “strengthen the soul” of their crafters. That make the “souls of their readers stronger, brighter, deeper.”

At the end of the day, that’s what there is to do. To use language for good—to write with integrity, in ways that enrich our lives and those of our communities. To honor the power of language—that living, dynamic system of communication that shapes our awareness and our connections to one another—by wielding it with care. And use it to save and preserve and nourish what is good, and to stem what is not.

Every time we sit down to write, we stand at that shoreline. We face that blank page, from which all good and ill begins.

And we stand, perhaps, on the threshold of hope, gazing with quiet awe at the dawn.

Cited Works

Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri, vol. 1 Inferno and vol. 2 Purgatorio, ed. and trans. Robert M. Durling, intro. and notes Ronald L. Martinez and Robert M. Durling. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1996, 2003.

Teodolinda Barolini, Commento Baroliniano, Digital Dante; Inferno 32-34, Purgatorio 1, https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/commento-baroliniano/.

Megan Garber, On Misdirection. New York: Zando/Atlantic Monthly Group, 2023.

Ursula K. Le Guin, “A Few Words to a Young Writer,” undated, https://www.ursulakleguin.com/a-few-words-to-a-young-writer.

Jane Siegel. “Illustrations from Early Printed Editions of the Commedia.” Digital Dante. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2017. https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/image/digitized-images/

"Death and life are in the power of the tongue," Proverbs something something. This is a lovely post. Can't wait to emerge to see, once more, the stars.

As I read this I couldn't help think of the words being used by Trump and Vance and all the other jackasses in politics including our new govenor and senator from WV. God help us all!

Pamela Martino