Friends, it’s such a joy to sit down and catch up with you. Today’s post shares how discovering a family cookbook from the 1920s last summer became an opportunity for me to reflect on household work, intergenerational memories, and to ask questions about how we all came (willing or not) to the kitchen.

Recipes from the farmhouse

Last summer, I was sorting through boxes in my parents’ house when I came across a few Saran-wrapped bundles. One turned out to be my great-grandmother’s cookbook.

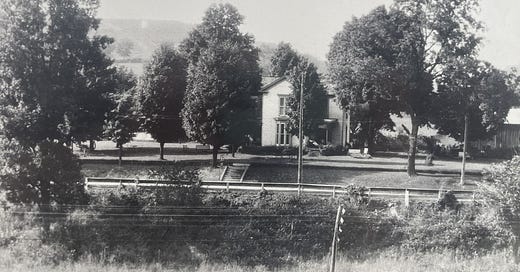

My mother’s maternal grandparents lived in West Virginia, in a white farmhouse that’s now gone, by a meadow where there once was a stream and ponies. They lived off the land: he kept bees and shot rabbits, grew vegetables and traded them with neighbors for milk and other goods. They took boarders and rented little cabins to railroad workers.

I would have loved to have a stronger connection to my family’s cooking past: my maternal grandmother learned how to cook from her Italian in-laws, who came to the U.S. from the Avellino province of Campania, and my paternal grandfather was a cook in the Merchant Marines during WWII and later in Italian delis in Manhattan. But this unexpected, Saran-wrapped culinary time capsule felt distant in time and in culture—unlike the food I grew up with in Puerto Rico or the Italian food I ate with my family in Brooklyn. Still, I was curious to read more.

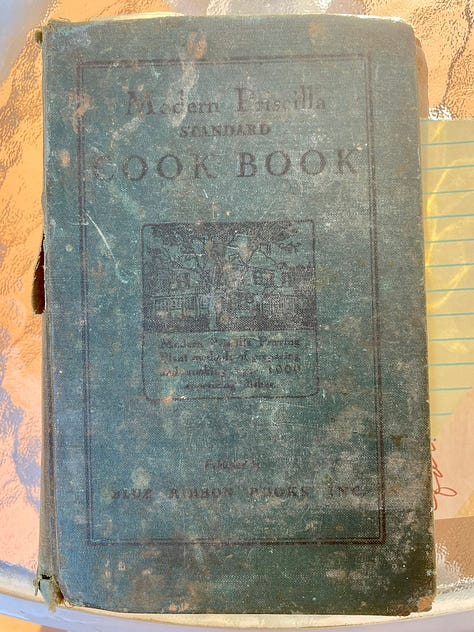

Gram’s Modern Pricilla Standard Cookbook was full of retro curiosities: junket, gelatins, cornflake macaroons, ginger ale jelly, coffee jelly, prune soufflé, deviled spaghetti, and jellied meat loaf. Here’s a few more (I can’t resist): clam patties, blushing bunny (a cheese concoction); melted cheese in a double boiler with canned tomato soup; baked tomato with liver stuffing, vegetable peanut butter loaf; sea moss blanc mange (Irish moss).

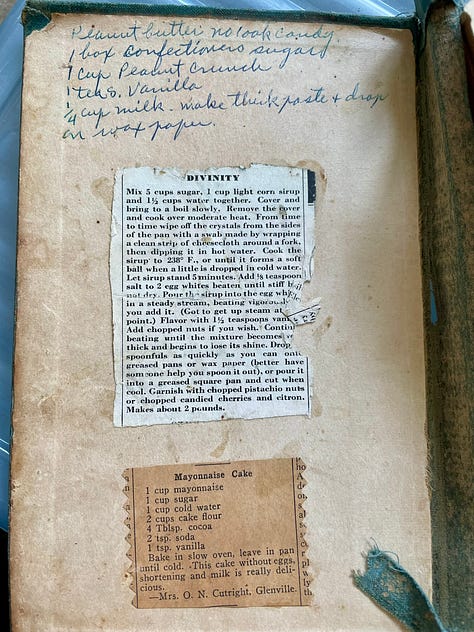

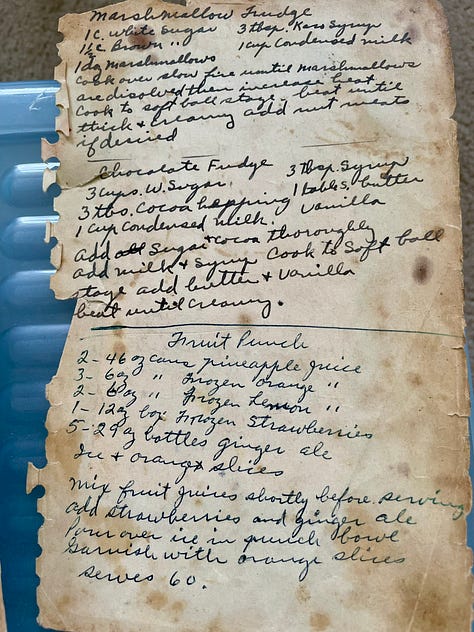

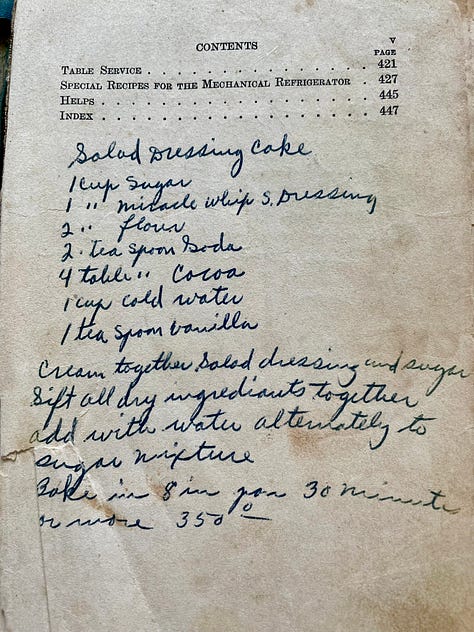

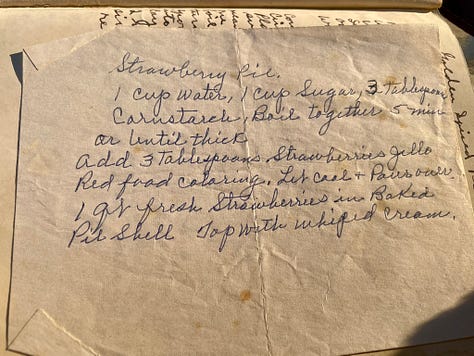

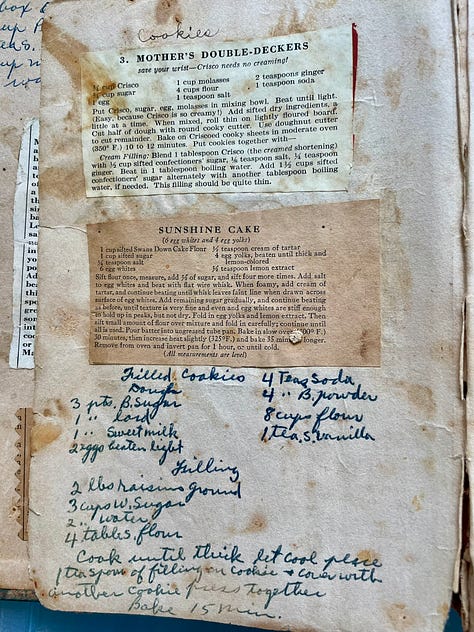

Gram included handwritten recipes from family members and pasted newspaper clippings on the book’s boards. Here was a deeply participatory food culture where women crowdsourced knowledge. Most of Gram’s handwritten recipes were of desserts. Mom said that Gram always did have a sweet tooth.

What her cookbook represents, for me, is not only a physical link to the farmhouse kitchen I remember from summer trips there as a child—the one with a handpump for well water and a root cellar below the backdoor stairs and the dining room where I first had blueberry pie.

It represents the meeting of agrarian food cultures and science-based, industrial food. The meeting of local food practices and the consumerist habits that would come to define mid-century, middle-class cooking. Mashups of Victorian gelatin dessert with prudent, limited-ingredient substitutions. What I was witnessing in Gram’s cookbook was the filtering of gastronomic knowledge, its dispersal through material culture, and its imbrication with corporate media—in this case, women’s periodicals. Cookbooks like this, like home economics programs, were at the forefront of teaching (mostly) women how to be consumers in a new grocery landscape. But folks at the farmhouse were still irrevocably connected to the food grown on their land.

Household labor, feminist economics, & domestic knowledges

It's taken me a while to appreciate cookbooks. Other than the boxed-mix cakes that my mother and I made, cooking was a perfunctory chore when I was growing up—not a task of creative inspiration. We often ate out in the many great restaurants in San Juan instead. I never really learned how to cook from my family, other than helping my grandmother hand-crank canned roma tomatoes for her homemade sauce—though I saw clearly how much work it entailed.

In some ways, I’m ambivalent about the legacies of domestic knowledge. Home cooking is still caught up in a system of gendered labor that women largely shoulder. Issues of feminist economics, household labor, and workforce inclusion and equity still feel very immediate—whether it’s in daily life or in media firestorms about homemaking or #tradwife influencers. The discourse of “housework” as workplace code for for invisible, uncompensated, and unrecognized service work—disproportionately allocated to women—shows that these structures also contribute to inequity in professional settings.

At the same time, I remember how my grandmothers expressed their love through this kind of cooking and nourishment—and how impactful that was to me. I’ve learned about bell hooks’s description of how Black women create homeplaces as a site of resistance against systemic racism and as refuges of radical care and self-determination.

It’s this theme of care—of the self, family, and community—that I want to lean into today to better understand my own generation’s relationship with cooking at home.

A stack of old cookbooks and a network of friends

I got my start in the kitchen under the tutelage of friends, and accrued an assemblage of recipes that, over time, reflected the generous and talented people in my life.

My first culinary mentor was my voice teacher in high school, Mary Eberhart. Mary, who was in her 80s, taught me the recipes from two fabulously retro home-entertaining menus, featuring things like Steak Diane, Chicken Kiev, and rum-baked pears, and she hand-typed each recipe for me.

Since then, I’ve learned several new recipes from friends:

Abby: grilled cheese sandwiches and that West Virginia staple, pepperoni rolls

Rebecca: San Antonio-style gumbo with okra

Nicole: stewed beans (after I was wowed by a pot she brought over for Friendsgiving)

Callie: almond cherry Bundt cake

Andrea: a joint effort to master avgolemono soup

In this way, cooking became for me a kind of site of memory of friends, places, and moments—a way to feel connected to community and people I care about.

Along the way, I became interested in food history—in items like cacao, sugar, and spices whose modern consumption is tied to histories of colonialism and human exploitation in the Caribbean and beyond. In the future, I’d love to work more on ways to decolonize the way we think about and represent food in popular culture—an interest that has led to a search for historical cookbooks and curiosity about contemporary ones.

It turns out that food connects to everything important, from health to economics to family to ethics. I have found that my efforts to learn how to be a slightly more adept cook have been repaid tenfold in the experiences I’ve had with those who have shared their knowledge—and recipes—with me.

Cookbooks, at their best, bring you into the intimacies of the domestic and the sensual, into the craft and performance of dishes savored or shared. But I often found cookbooks inaccessible—in terms of knowledge, ingredients, equipment, budget, technique.

These cookbooks sometimes seemed aspirational or performative. Their full-bleed photos featured small groups of friends with very white teeth smiling as they lounged in a Sonoma-style landscape of space and ease, gathered around a gorgeous wooden table with matching flatware. When I invited friends over, it looked more like folks sitting around a cramped IKEA table or standing up, holding paper plates, shoes piled by the front door. There was a delightfulness to that. But it didn’t chime with the cookbooks I had. Instead, I leaned into decade-long subscription to Cooking Light, and I still have folders of clippings from that.

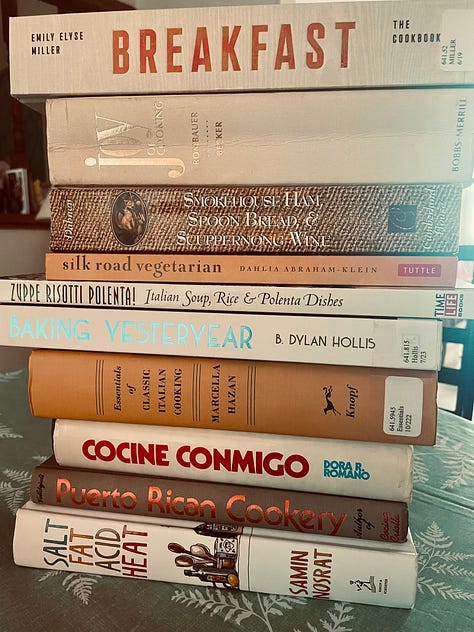

Alicia Kennedy writes that we all want different things from a cookbook. For my part, I enjoy cookbooks that share personal narratives, stories where chance and accident, auspiciousness or even tragedy, lead to the recipes. For me, Apollonia Poilâne’s coming-of-age narrative in Poilâne (2019) and calm, thorough explanations of craft are a lovely afternoon read. Marcella Hazan’s personal journey—including the bit about boiling a corpse’s head for her anatomy class during WWII—is completely unexpected and hard to forget. I’ve also enjoyed reading Dylan Hollis’s Baking Yesteryear, which draws from his archive of antique cookbooks and crowdsourced recipes. Baking Yesterday reminds me that there are different ways of doing history, including this revivification of older recipes in which experimentation, skepticism, and even “disgust” are allowed in a spirit of play and curiosity—rather than aspiration and expertise.

I did try one of Baking Yesteryear’s recipes with my mom (using the wrong flour, no less). Our “mayonnaise cake” ended up smelling like burned popcorn; I watched it in the oven as it started to edge up the side of the Bundt pan, like a bog monster getting ready to pull itself out of the swamp. Still, it was a fun and strange romp in the kitchen, and one I won’t soon forget.

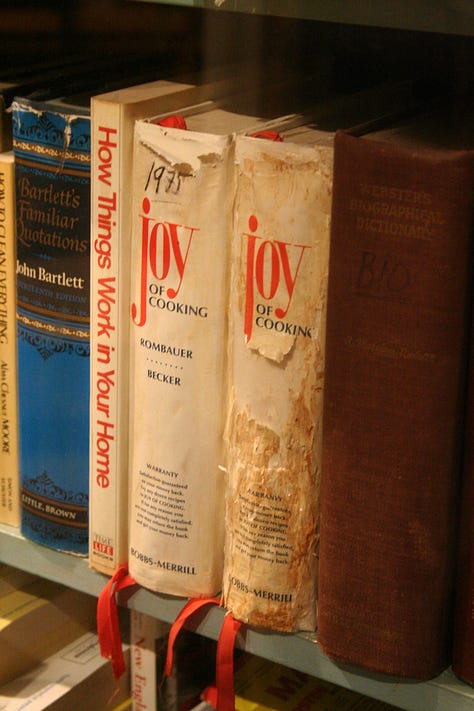

Joy of Cooking

I always use my mother’s Joy of Cooking when I’m at home—the 24th printing of the 1975 edition—rather than my newer paperback copy. The cookbook, written by Irma S. Rombauer and her daughter Marion Rombauer Becker, is its own kind of family epic—a story about Depression-era resilience and entrepreneurship and legacy.

The cookbook’s epigraph is a translation from Goethe’s Faust: “That which thy fathers have bequeathed to thee, earn it anew if thou wouldst possess it.” I find that encouraging. Domestic knowledge is not just an inheritance; it’s a legacy earned through study and labor.

Joy of Cooking, simply put, explained everything. As a child, it was the gnostic tome that my mother brought at Christmas to make Refrigerator Cookies. “The Foods We Heat” section discussions the various ways of actually cooking food, with an anecdote about a cook whose instructions to a beginner are: “Stand facing the stove” (145). Nothing is assumed, and everything is possible.

“Coffee has always thrived on adversity—just as people in adversity have thrived on coffee.” – Joy of Cooking

My mother learned the basics from Joy of Cooking in part because her own mother was so busy raising a large family and taking care of my grandfather—a busy obstetrician who was always going out on calls, day and night. Her favorite recipe, she told me, was Chicken Marengo. “We didn’t all grow up in our mothers’ kitchens,” Mom said. It’s intriguing to think that the very housework that women in my grandmother’s generation pursued (cooking, child care, domestic finances, etc.) could prevent them from having the creative space to compile and pass their knowledge on—if they wanted to.

In Joy of Cooking, you’ll find “Eggs in Aspic Cockaigne,” as well as tacos and glazed canapes, omelets made with brandy, crepes suzette (a Victorian creation from accident), as well as salads, canapes, griddle cakes, fritters, breads, and many more. You’ll also find the vitamin count of avocadoes, quotes from Charles Lamb, and reflections on frog legs that twitch.

Reading Joy of Cooking today (even our nearly 50-year-old edition), I’m struck by its witticisms and modernity. The authors state the need for dependable information as a bulwark against the “oversimplified and frequently ill-founded dicta of food faddists that can lure us into downright harm” (1). They advocate for using fresh, whole foods “with minimal but safe processing and preservatives and without synthetic additives” (1).

There’s a breathless comprehensiveness to its coverage of offal and even boiled brain, which now links the realities of Depression-era cooking with contemporary snout-to-tail butchery. There’s also hard-to-unsee illustrated instructions for skinning a squirrel in the “game” section.

The original cover illustration of the Joy of Cooking, designed by Marion Rombauer (Irma’s daughter), featured St. Martha of Bethany slaying a dragon—the “dragon of kitchen drudgery,” according to the Simon and Schuster website (let us remember that Irma herself had a cook). St. Martha became known in Christian exegesis as representative of the vita active (or active life) with the work of hospitality and food preparation.

I like to think of Martha’s dragon in Joy of Cooking—the product, in some ways, of Depression-era experience—as transforming with each era in which the cookbook was used. The dragon reminds me of the wolf at the door in M. F. K. Fisher’s How to Cook a Wolf—a specter of the very real, everyday obstacles faced by those living through challenging times.

And I imagine that some readers used the cookbook to transform domestic knowledge into a strategy of creative resistance—much as described by Michel de Certeau in The Practice of Everyday Life—as a knowledge base to pursue their own journeys in life supplied with the information they would need to nourish themselves along the way.

The legacy of “Joy”

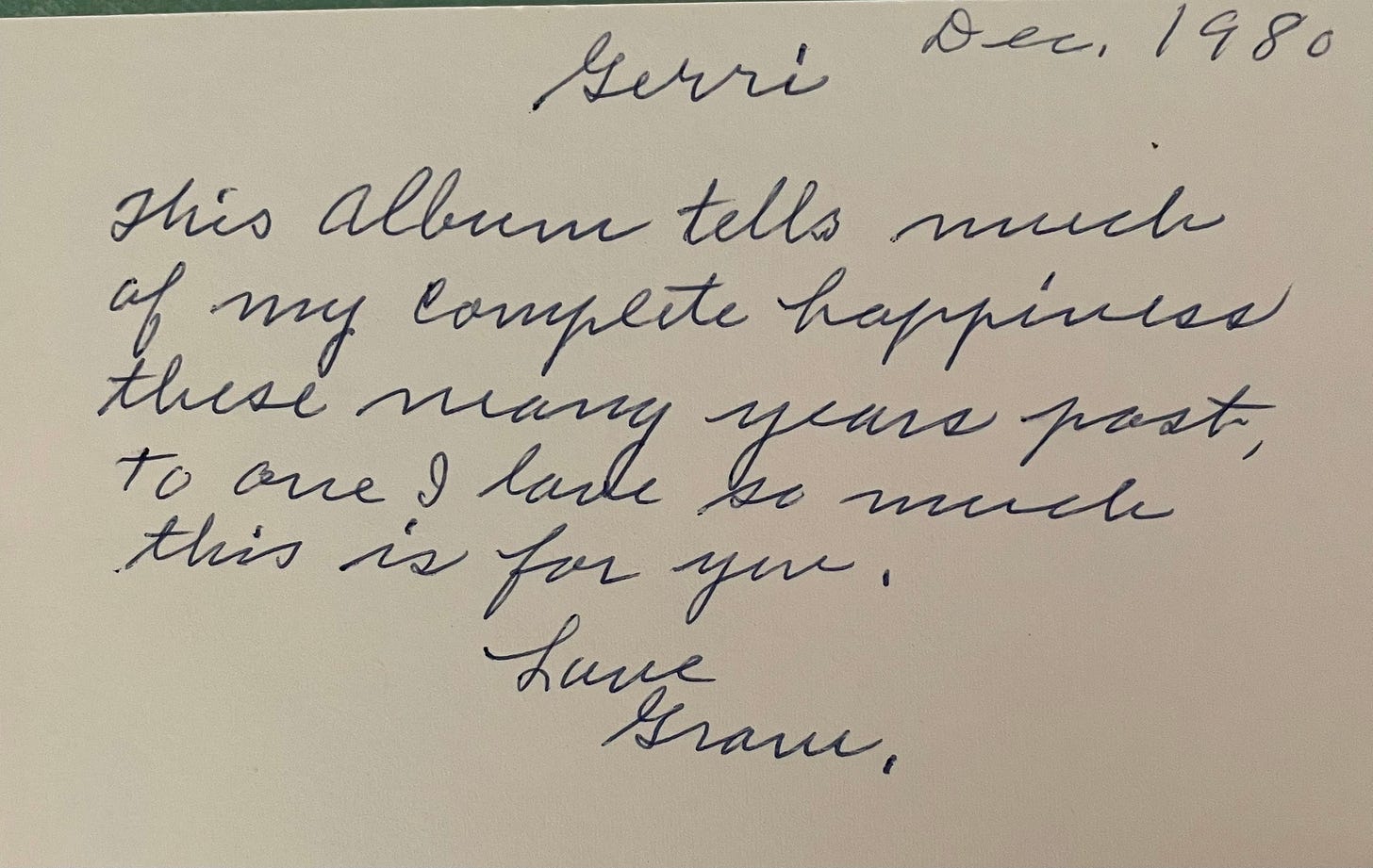

A few years before I was born, Gram created an album for my mother with pictures and clippings from family celebrations (graduations, marriages, births, plays my mother had been in). She included a note in the album that read: “This album tells much of my complete happiness these many years past, to one I love so much this is for you.”

This was the legacy I had been searching for all along: the celebration of a life lived wholly, one whose labor held meaning and purpose. The realization that within the historical circumstances they had lived, the women who came before me pursued meaningful lives, experienced joy, and savored and shared it with those they loved. They nourished their families and communities, and celebrated the various paths taken by their children.

I’ll be adding Gram’s handwritten recipe for chocolate fudge to my collection—and perhaps, if I’m brave, the salad dressing cake recipe, too.

I’m still learning!: I’d love to hear from you about a recipe you’ve learned from friends, family, or favorite cookbooks. Feel free to reply below, or to share information about organizations that contribute to local agriculture and food equity.

And if you enjoyed this post, please forward it to someone else who might enjoy it too!

Bonus: Gram’s Salad-Dressing Cake Recipe

1 cup sugar

1 cup Miracle Whip salad dressing

2 cups flour

2 teaspoons soda (baking soda, I presume)

4 tablespoons cocoa

1 cup cold water

1 teaspoon vanilla

Cream together salad dressing and sugar. Sift all dry ingredients together; then add [to this] water alternatingly with sugar mixture.

Bake in 8 inch pan 30 minutes or more at 350 degrees F.

Further Reading:

Megan Brenan, “Women Still Handle Main Household Tasks in the U.S.,” Gallup.com, January 29, 2020, < https://news.gallup.com/poll/283979/women-handle-main-household-tasks.aspx>

Allison Daminger, “The Cognitive Dimension of Household Labor,” American Sociological Review, 84.4 (2019), pp. 609-33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419859007

“Food Revolutions: Science and Nutrition, 1700-1950,” University of Missouri Special Collections Digital Resource, https://library.missouri.edu/specialcollections/exhibits/show/food/health/domestic-science.

Pierre Franey, “Chicken Marengo,” NY Times Recipes, https://cooking.nytimes.com/recipes/1018865-chicken-marengo.

Sarah Jane Glynn, “An Unequal Division of Labor: How Equitable Workplace Policies Would Benefit Working Mothers,” AmericanProgress.org, May 18, 2018, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/unequal-division-labor.

“Home Economics — Domestic Science,” Library Guide, University of Wisconsin, https://www.library.wisc.edu/gwslibrarian/bibliographies/science/home-economics/

bell hooks, “Homeplace (a site of resistance),” in Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics. Boston: South End Press, 1900, pp. 41-49.

M. Järvinen and N. Mik-Meyer (2024). Giving and receiving: Gendered service work in academia. Current Sociology https://doi.org/10.1177/00113921231224754

Kat Kinsman, “Ode to Joy: The powerful legacy of Joy of Cooking, America’s favorite cookbook,” Food and Wine, Nov. 16, 2018, https://www.foodandwine.com/lifestyle/books/joy-of-cooking., 20

Liz Mayo, “Women Do Higher Ed’s Chores. That Must Change,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, February 13, 2023, https://www.chronicle.com/article/women-do-higher-eds-chores-that-must-change.

Anne Mendelson, Stand Facing the Stove: The Story of the Women Who Gave America the Joy of Cooking (New York: H. Holt, 1996). https://archive.org/details/standfacingstove00mend/page/n7/mode/2up

Helen Rosner, “The Strange, Uplifting Tale of ‘Joy of Cooking’ Versus the Food Scientist,” New Yorker, March 21, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/annals-of-gastronomy/the-strange-uplifting-tale-of-joy-of-cooking-versus-the-food-scientist.

Additional image credits

Jean Poyer (illustrator), Hours of Henry VIII: Saint Martha Tamming the Tarasque (c. 1500). France, Tours. Morgan Library & Museum, MS H.8, fol. 191v. https://www.themorgan.org/shop/st-martha-taming-tarasque

Saint Martha, Flemish illumination from the Isabella Breviary, 1497. http://www.akg-images.com/akg_couk/_customer/london/collections/britishlibrary.html

Diego Velazquez, “Christ in the House of Mary and Martha” (1618), National Gallery, London - online collection, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9459265